On the day that I met Wiley I was with three women from a well-to-do Baptist church in the center of Newnan. They belong to a group that delivers meals to the area’s poor. On this day, their route led them out into the country, to a mill village that had been built by the Arnco cotton mills, in the 1920s. As our car rolled into the neighborhood and stitched through the narrow streets, it was easy to imagine an earlier time, with men carrying lunchboxes to a humming mill, children playing ball in a nearby field, families on Sunday walking to church. Now, since the mills in the area had closed, in the 1950s, the streets were rutted, empty. The village had become known as a place of poverty, addiction, and crime.

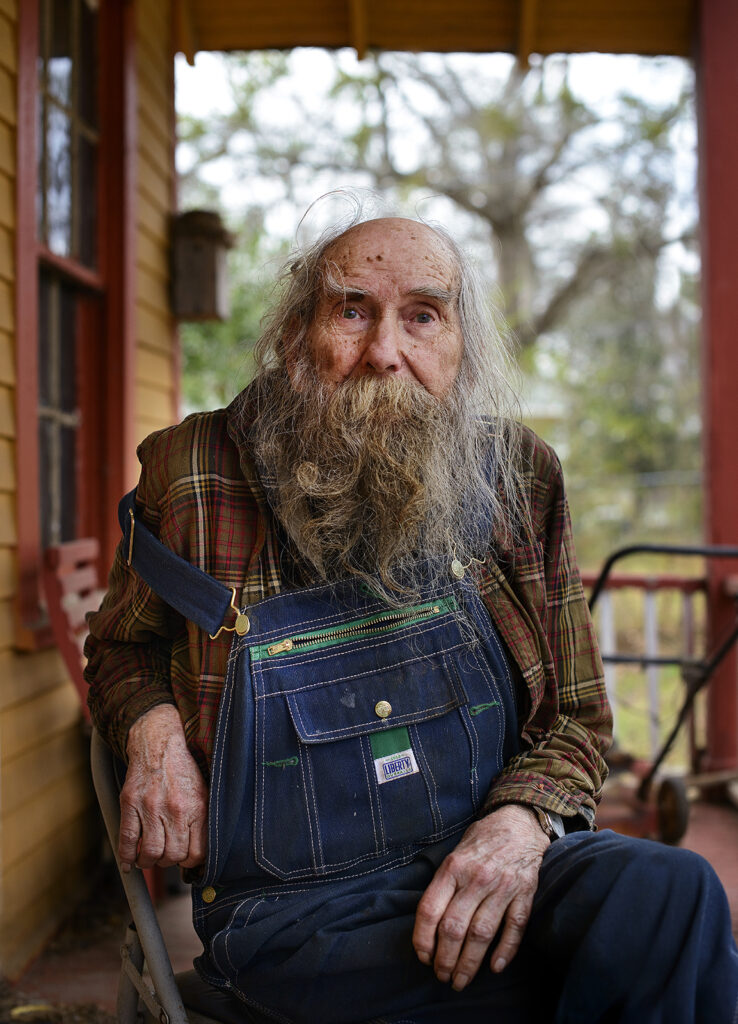

We stopped at a mustard-colored house with a sinking front porch, and an elderly man appeared at the door. One of the women handed him a meal in a container with a Bible verse on top – and he said, “Thank you.” I asked the man if I could visit him on another day.

A few days later, I went back to visit the man. He told me that his name was Wiley, and that he had lived in the village for many years, although he couldn’t remember exactly how many. He had worked in the Arnco Mill in the packing department, folding the manufactured blankets, and then wrapping them for shipment. He’d retired years before, though he couldn’t remember exactly when. He told me he had a son, on the West Coast, and a daughter, who lived nearby.

I made a portrait of Wiley on his porch, and then he showed me around his house, a tiny four-room bungalow typical of an old mill village. Moving through a home that had been long neglected – the walls Blackened with fireplace smoke and the corners covered in cobwebs – he showed me his pellet gun and his gospel records, and some faded photographs. On the mantel stood a photo-studio portrait of a couple, and I recognized a young Wiley; the woman was his wife, he said, now deceased.

I visited Wiley again, to give him a copy of his portrait, and I called his daughter to learn more about him. She told me that when she was small they had rented a shotgun house in a mill village farther north, but that he’d bought his house in Arnco when the mill offered its employees the village houses for purchase. She told me that he’d lived with a lot of pain, after a career of packing and hauling heavy loads. In his old age he loved to eat at the Waffle House, and to sift through yard sales, where he’d buy pocket knives and old lawn mowers, to tinker with.

The following year, I went out to Arnco to see Wiley again. This time the doors of his house were wide open, the rooms were nearly empty, and two people were burning brush in the back yard. A young man approached, and told me that he had bought the house. I noticed he spoke with an accent, and asked where he was from. He said he was from Peru. He told me that the previous owner had passed away.