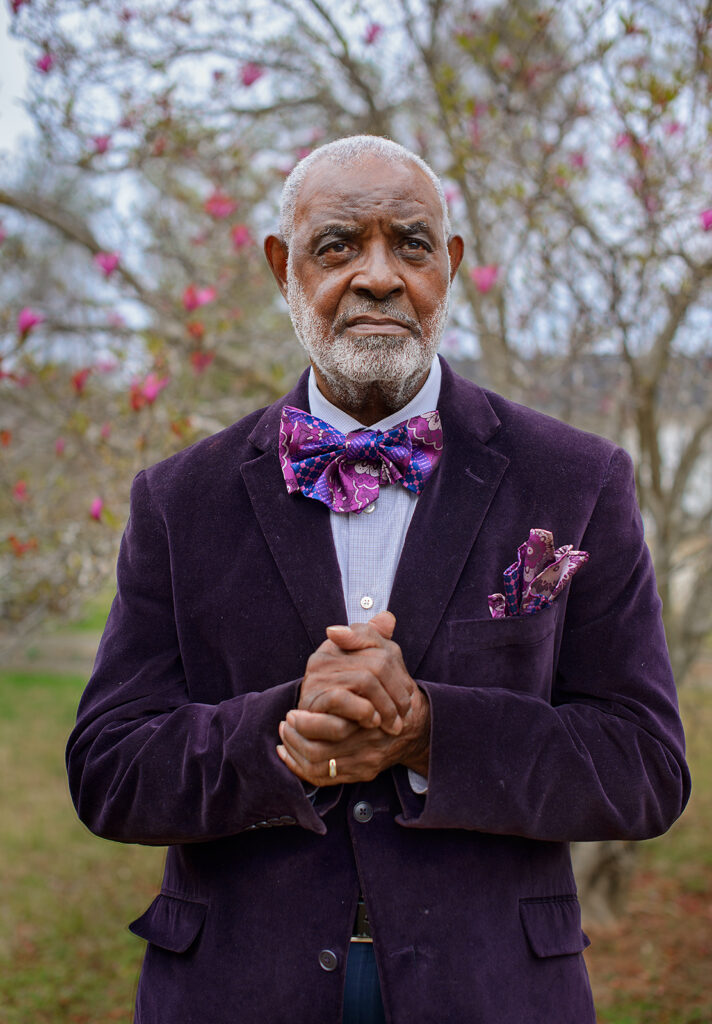

Gospel music was filling the air in the largest black church in Coweta County when I first saw Rufus. I was with a friend who’d invited me to the concert, a fundraiser for a man in the congregation who had cancer. Rufus was wearing a plum-colored velvet jacket and a handkerchief and matching bow tie; as he passed us he said “Hello” to my friend, and seemed to glide as he walked. “He’s like a black Sean Connery,” she said, after I’d asked about the elegant man. She told me that he was a pastor in the community, and that recently at Walmart he’d come up to her and said, “Anybody told you they love you today?”

Days later I contacted Rufus and went to see him at his home. He lives some eight miles from the center of Newnan, on a long country road named after his father. With only a third-grade education, his father had built up a successful farm, where he raised Rufus and his 13 siblings. When Rufus was a boy, in the 1950s, there was no bus for black people, so his father would take him in his pickup truck to Newnan, to stay with an old widowed aunt while he attended the “colored school.” At the end of the week, his father would bring him back home.

After he was grown, when he was newly married and working as a truck driver, Rufus was sitting in his truck one day feeling depressed and reading the Bible. Suddenly he was overcome by a pull in his stomach and a sweetness in his mouth. He told me that he knew he’d been struck by the word of God, who was telling him to become a preacher. “I cried like a baby,” he said, “because that’s not what I wanted to do.”

Then, he said, he remembered that his father’s father had been a minister, and he accepted the call. His grandfather had graduated from Morehouse College, the prestigious black men’s college in Atlanta, and had built churches all over the area. “My granddaddy on my dad’s side had cotton mills, and he had hands, cotton gins, and he had a big farm.” I asked how this black man, whose son had only a third-grade education, had amassed so much capital in the segregated South.

Rufus said that he didn’t quite know. But then he offered this: “Both of my great-granddaddies were white. And we know that my great-great-granddaddy and great-great-great-granddaddy were white. I’m so mixed up I don’t even know who I am. If you was to see the picture of my grandmother, she probably looked like you.”

Rufus continued, “I sit here and tell you I don’t know who I am, because I’m mixed and I know I’m mixed. . . . Since everybody’s all mixed up, what does that mean? If you don’t love everybody, then you’re mixed up, too.”

What followed after he told me this was a wide-ranging, hours-long conversation: about the history of Newnan; the legacy there of discrimination, exclusion, and violence; and the categories of race that people have built to exert power over one another. I asked him what he thought his community needed.

“Out of one blood God made all nations,” he replied, “and when we come to that, we can stop fighting among ourselves. We can start loving one another, as God loves us. This is what our community needs.

“If we can’t do it here, where can we do it? You can’t wait to get to heaven and say, ‘Okay, I’m going to love you.’ You’ve got to do this here, and you’ve got to show it.”